13 Jul 2023 Paper on the Russian philosophy of language published

A paper on the Russian philosophy of language has been published in the Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 22 (65), 2023: 145-58.

Words to things: religious cosmologies in the context of the (Russian) Orthodox philosophy of language

Abstract

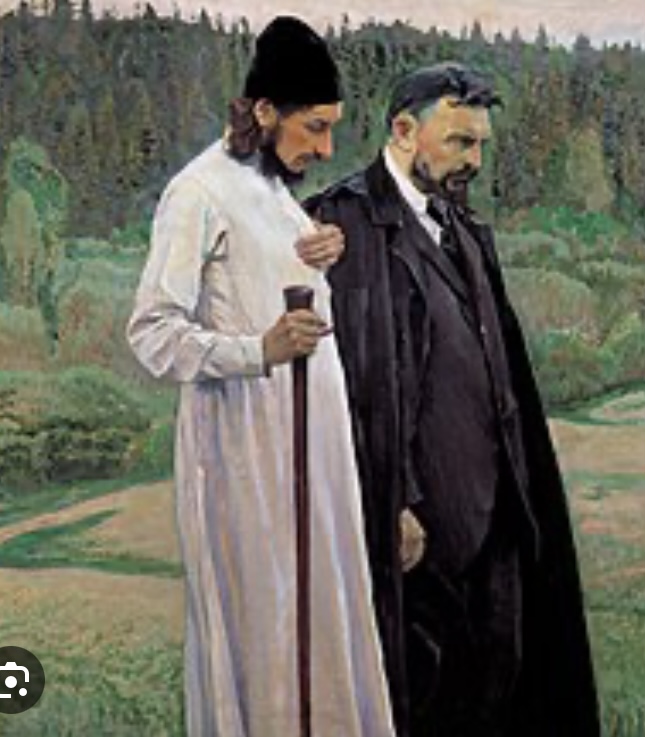

Religious cosmologies put forward by Russian philosophers and thinkers at the beginning of the last century had important things to say about the linguistic construction of personhood and the relations between words and reality. Not shying away from personal phenomenologies which regard words as cosmic self-expression, these philosophers help us rediscover both the sensuality and physicality of language. This article explores how such apparently long forgotten philosophies of language live on to some degree in religious Orthodox practice in Russia today. What is more, it serves to remind us of the connections between language, spirituality and the sacred. By engaging with the spirit of prophecy, thinkers such as Bulgakov (and indeed some contemporary worshippers) show us the significance of what it means to ‘feel’ language.

Keywords: Orthodox; philosophy; language; sacred; word

Introduction

What is the correlation between a word and the reality it designates? How are words animated by meaning, how are word-reality relations cosmologised in a liturgical context? To understand this, we tend to resort to theories regarding what is perceived to be the conventionalised nature of the sign, or as in the case of non-western epistemologies to some kind of indeterminate cosmic force. With regards to the latter, there was in the first half of the twentieth century an ill-defined group of Russian philosophers, poets, philologists and theologians who were convinced that we had underestimated the significance of these indeterminate cosmic forces. In this article, I will be unwrapping some of their views in the context of sacred, liturgical language.

More specifically, I wish here to explore what one might call alternative theories of signification put forward by these so-called Orthodox philosophers to try to understand better the complex ways word-reality relations are mediated and experienced amongst Russian Orthodox Christians (Part 1979, 1-29). The so-called ‘Orthodox Philosophy of Language’ came about after the imiaslavie dispute in 1912 concerning what was perceived to be the glorification of the name of God. A group of highly original thinkers developed a series of interrelated ideas and theories about the internal form of the word. Many of these thinkers took their inspiration from the mystical theology of the Orthodox Church. Here, these theories of signification and sign-interpreting consciousness are examined in the context of long-term ethnographic fieldwork carried out amongst Orthodox Christians in Moscow.

Many of these unconventional thinkers hoped to show that a disembodied approach to signification might benefit greatly from embracing more holistic, Eastern ontologies of language. Yogi speak in terms of cosmic life forces (prana); all the philosophers, poets, linguists and thinkers that comprise this group of intellectuals speak in terms of the ‘cosmic force’ (kosmicheskaya sila) of the word without the need to define what they mean by this. It was apparently assumed that the Russian readership would understand instinctively such a notion. There was an understanding that a word can be infused with such a cosmic force and that this endowment comes from a greater uniting power, be it consciousness, some kind of spiritual endowment or God.

Whilst this group of thinkers seldom speak explicitly of phenomenology in their works even if some of them (such as Shpet 2006 and Losev 1990) were clearly influenced by phenomenological thinking, their pronouncements on the word should be seen as phenomenological. They wanted to revitalise the experiential bond with the ‘word’ which they perceived to be fundamental to the constitution and coherence of the Self. Similarly, when discussing complex relations with icons and Church Slavonic (the liturgical language), my interlocutors would often unknowingly employ phenomenological interpretations talking in terms of reciprocal energy flows and how prayer can bring about an ‘embodied enmeshment in the world’ (voploshchennayasvyaz z mirom).

Opposing ideologies of language based on the conventionalisation of the form-meaning relationship (Leonard 2021, 1-26; Jakobson and Hrushovski 1980, 33-38), these thinkers wished instead to engage with the phenomenological notion that the word lives in itself and for itself, that it can be absolutely self-sufficient. To put this into context, before one Easter Divine Liturgy, I spent an afternoon talking to an elderly parishioner called Andrei. We were discussing the status and reception of Church Slavonic when he said (author’s translation):

V etikh svyashchennykh slovakh tozhe yest’ zhizn’. Iz pokoleniya v pokoleniye oni peredayutsya ot Boga k nam cherez svyashchennika. Oni zhivut v etikh svyatykh mestakh, no pachti ne syshestvyut za predelami etikh sten.

These sacred words have a life too. For generations, they are passed down from God to us through the priest. They live in these holy places, but have little existence beyond these walls.

This was a perfectly Bakhtinian (1981, 345) declaration; the idea that the word is the product of the interrelation between speaker and listener (here God and church-goer). It was such insights that guided my ethnographic inquiry. As we will come onto see, both the opinions of my interlocutors and those of the Orthodox philosophers point to a theory of signification that considers the totality of cultural and linguistic practice and lived experience. In this article, I hope to show that there is every reason to believe that we need more ontological, relational approaches and understandings of language that are linked to the sensual and holistic, and that are organically connected to life.

Background

Despite the seventy-four years of the Soviet Union, the Russian Revolution and the dawn of secularist thinking, the word-reality relations that seem to lie at the heart of Orthodox thinking continue to live on and index all the mysticality so stereotypical of Russian spirituality. Orthodoxy’s belief systems have been sustained in words and customs. Indeed, the appeal of Orthodoxy for thinkers like Rozanov was its words and the supposed truth that could be found in its rituals (and not catechism). Similarly, Bulgakov (1917, 155; 158; 369) spoke of words as ‘vessels of grace’ and believed that truth can only be revealed. It cannot be gained from acquiring knowledge or rational synthesis. Eastern Christianity is not wedded to any kind of Socratic quest for knowledge; it is experiential (actual knowledge is obtained through practice where ‘actions outweigh intentions’ (Luehrmann 2017, 163-84), and it is not surprising that both Rozanov and contemporary Russian Orthodox worshippers alike are inclined towards a more experiential approach to language.

However, Rozanov also understood that the mechanical and repetitive nature of religious rituals meant that there was a risk that they would become meaningless. A corollary to this is of course language itself. As Malinowski (1923, 296; 309ff) pointed out, much of language in daily use is semantically vacuous. Conscious of this, the Orthodox philosophers and poets were appealing to some kind of phenomenon that would be the diametrical opposite of Malinowski’s ‘phatic communion’. Instead of ‘small talk’ or what Bulgakov (1953, 128) calls pyusto slovii (‘empty talk’), they wanted each utterance to be replete with meaning and performative power. For this to come about, Bulgakov (1953, 153) wanted us to embrace the idea that there is a unity between language and thought and that this is ordained by the Holy Spirit.

As we will see, certain registers such as sacred language can produce a particular set of experiences in its speakers because it is felt with our bodies. For example, through the embodied experience of the priest’s voice speaking Church Slavonic, language becomes for a small number of my interlocutors an integral aspect of what it means to feel God. These kinds of speaker experiences are personal and require a phenomenological foundation. As Lindholm (2002, 335) has observed, in the fluid world of modernity there is a tendency for people to retreat to their inner world in search of meaning and authenticity. The mysticism of the Divine Liturgy is one such avenue into that inner world – the chanting – the repeated enactment of a given sacred world in words. For some, the language in their inner sense might have some kind of incantatory power. The language of these services – this theatrical production (liturgy is dramaturgy) – is embodied in various ways and of course is intertwined with sensory experience (Ochs, 2012, 142-60).

The ontological properties of the sign

So, according to contemporary Russian Orthodox Christians, what are these ontological properties of the sign? Just as Bulgakov (1953), Potebnia (1976), Shpet (2006) and Losev (1990) tended to do, many worshippers still like to speak of ‘the soul of the word’ (dusha slova) – a word’s inner form is perceived to emanate from the spiritual ‘verbal cosmos’ and like an icon, the inner form has an image like quality. Both Sergius Bulgakov and Losev believed that voice is the body of the word and the index of emotional meaning, but the voice is not a homogenous thing and so a word can have a myriad of acoustic permutations. Voice is a category invoked in discourses about personal agency, cultural authenticity and political power (Weidman, 2014:38), and the theme of the sonic dimensions of voice has recently been studied by a number of scholars (Kunreuther 2006, 323-53; 2010, 334-51; 2014; Weidman 2006; 2014, 37-51; Harkness 2011, 99-123; 2014; Faudree 2012, 519-36; Briggs 2014, 312-43; Jacobsen-Bia 2014, 385-410).

Bulgakov highlighted the point that each word and voice has its own noema where meaning is derived from a specific word uttered by a specific person and at a specific time. The noema points to the opposition between the objective essence of the word and the subject perceiving this essence. Each word carries shades of meaning depending on voice and intonation, and it is in part these permutations that make speech feel ‘alive’ (zhivoi) because it represents the embodiment of feelings.

For the Christian worshippers that I worked with in Moscow, the ‘soul of the word’ was tantamount to the ‘essence of the word’ (sushchnosti slova) as the source of the word’s ontological characteristics – the essence of speech was often described as an ‘awakening of meanings’ (probuzhdeniye smyslov). Bulgakov (1953, 22) said it is this awakening of meanings that connect the consciousness of people. An appreciation of words should begin with intuition (nuzhna intuitsiya slova), I was once told at a discussion in a local church about the meaning of a certain chant in the Divine Liturgy. The same parishioner told me that sacred language was a system of communicative practice that requires a different interaction from regular, everyday language use and can result in a different kind of subjective experience. In the same vein, the Russian phenomenologist, Shpet,(2006, 26) believed that we understand each other, not because of the mutual acceptance of theconventionalisation of the sign, but because:

a potomu, chto oni kasayutsya odnogo zvena v tsepi chuvstvennykh predstavleniy i vnutrennego porozhdeniya ponyatiya, kasayutsya toy zhe struny svoyego dukhovnogo instrumenta, vsledstviye chego v kazhdom i vyzyvayutsya sootvetstvuyushchiye, khotya i ne tozhdestvennyye, ponyatiya.

but because they touch one link in the chain of sensory representations and the inner generation of the concept, they touch the same string of their spiritual instrument, as a result of which the corresponding, although not identical, concepts are evoked in each.

The Russian theologian, Bulgakov (1953), did not endorse the conventionality of the sign either by which I mean the Saussurean hypothesis that the relationship between form and meaning is arbitrary. Bulgakov recognised that the logos has a double nature (1953, 24) – word and thought, body and meaning – but he believed these elements are indivisibly merged. Moreover, he perceived words to be symbolic in naturebecause they not only represent things, but also reflect the internal processes of knowing the subject. Symbols are not arbitrary, but are external subjective signs that are naturally connected with the idea they convey. Such opinions problematise the dominant Euro-American ideology that compels us to believe that language functions as ‘a transparent medium of representation’ (Summerson Carr 2013, 46). However, Bulgakov believed that this said symbolism was extinguished when the inner form is exhaled in the sound of the word. The symbolism wanes when abstract thought turns the word from an end in itself (an aesthetic phenomenon) into a tool.

Bulgakov’s predecessor, Potebnia – the philologist and Slavicist – spoke of how a philosophy of language should begin with a konkretnoy dannosti slova (‘the concrete givenness of the word’) and ne ot logicheskoy yego dannosti (‘not from its logical givenness). By the ‘concrete givenness of the word’, he meant the articulation of the word is an echo of the state of the soul. With his Platonic thinking, Bulgakov spoke of how the word is a unity of matter and spirit. These ideas became a recurring theme in my fieldwork. Parishioners told me on a number of occasions: ‘The soul shines forth from the words of the Divine Liturgy’ (dusha siyayet ot slov bozhestvennoy liturgii).

As well as striking an anti-rationalist, anti-deductionist tone, thinkers such as Bulgakov, Shpet and Rozanov were concerned how the heteronomous nature of everyday speech brought about the ‘death’ of the inner form of the word. Not generally versed in the Orthodox philosophers’ views on the inner form of the word, my interlocutors also spoke nonetheless unwittingly of the mysticism of sacred language and how its potential demise could impoverish spiritual life. To be clear, they didn’t make reference to the ‘spiritual verbal cosmos’ in the way that Bulgakov (1953, 123) does, but when discussing the Church Slavonic language (often in the context of why it should remain the language of the Church), they frequently invoked the idea that like an icon the inner forms of sacred words have an image like quality.

Avtor: kakoye znacheniye dlya vas imeyet tserkovnoslavyanskiy yazyk?

Tat’yana: Dlya menya eto svyashchennyy yazyk. On funktsioniruyet kak vorota ili portal k dukhovnosti. Yesli izmenit’ yazyk tserkvi, eto vse ravno, chto ubrat’ ikony. Vy menyayete dukhovnost’ lyudey. Eti slova, oni prosto kak-to podnimayutsya vnutri tebya.

Author: what is the significance of the Church Slavonic language for you?

Tatiana (an interlocutor): For me, this is a sacred language. It functions like a gateway or portal to spirituality. If you change the language of the Church, it is like removing icons. You change the spirituality of the people. These words, they just rise up inside of you somehow.

For Tatiana, no explanation for the origination of words was required. For Bulgakov (1953, 148) too, the ‘birth’ of words was a grandiose cosmic process of self-ideation of the Universe. He held that words are not created according to conventions, but instead express themselves in and through their speakers:

It remains simply, humbly and devoutly to recognize that it is not we who speak words, but words, sounding in us interiorly, speak themselves…. The world speaks in us; the entire universe, not us, sounds its voice…. A word is the world, for it is the world that thinks itself and speaks; however, the world is not a word, or rather it is not only a word, for it still has meta-logical, nonverbal being. A word is cosmic in its nature, but it belongs not to consciousness alone, where it blazes up, but to being, and the human being is the world’s arena, the microcosm, for in it and through it the world sounds (author’s translation)

My interlocutors made oblique references to what you might call the multi-dimensionality or the interiority of the word (Descola 2013 [2005]; Leonard 2021, 1-26) – the kind of reflections that shape the subjectivities vis-à-vis the word:

Tat’yana: Dlya menya liturgicheskiy yazyk — eto yazyk, osnovannyy na metaforakh. Ya chuvstvuyu, chto eti slova bogaty simvolami. U nikh yest’ drugoy sloy, eti slova ne prosto predstavlyayut zvuki. Yesli vy smozhete prinyat’ logos, togda vy smozhete nayti Boga. Vy mozhete stat’ bozhestvennym Sushchestvom

Tatiana: For me, the liturgical language is a language rooted in metaphor. I feel like these words are rich in symbols. They have this other layer, these words don’t just represent sounds. If you can embrace the Logos, then you can find God. You can become a divine Being

It was clear to me that devout worshippers found some kind of ontological security in these beliefs. For many Orthodox Christians, sacred words and rituals are suspended in some kind of atemporal dimension and there is an urge to discover the Self in this linguistic and aesthetic dimension through perhaps prayer and the imbued symbolism of the Divine Liturgy, where it was clear that both for them (and me alike) the ‘tension of consciousness’ (Schütz and Kersten 1976, 5) could change.

Contemporary Orthodox worship and Russian religious philosophy of language of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century seemed to share then something in common: a search for interiority and relating that interiority to the outside world. Amidst this interiority came the notion that the locus of language is the complex dialectical interplay between objectivity and subjectivity. One might refer to this as the ontological efficacy of language where language indicates the metaphysical properties of the Self. The basic idea is that language is continuous with essence. Echoes of these Orthodox philosophers’ views can still be found amongst church-goers today: ‘A word is a thought and thought is the word itself’, as one worshipper and part time theologian told me.

In defence of ‘sacred’ words

I asked one of my younger interlocutors, Alina, what for her was a ‘sacred language’. After a short pause, she said:

Svyashchennyy yazyk — eto odin iz sposobov, kotorym Bog dayet znat’ o svoyem prisutstvii.

A sacred language is one way in which God makes his presence known.

There has been much written about what actually comprises ‘sacred’ language (Durkheim 1961; Haeri 2003; Leonard 2021b, 140-158), but our starting point might be a semiotic one. By and large, my interlocutors did not necessarily believe that the relation between linguistic forms of ‘sacred’ words by which they meant Church Slavonic words that were used in the Divine Liturgy and their corresponding meanings was arbitrary. They weren’t perceived to be arbitrary because these words are considered not only to be imbued with a divine energy, but a multi-referentiality can in fact be attributed to them. These words are both meaning and cosmic force. Bulgakov (1953, 212) would have us believe they are ‘spiritual principles organised by phonetic matter’; they are both a spontaneous force and a repository of ‘magic’. In order to be able to feel this ‘energy’ and ‘cosmic force’, he believed that you needed a consciousness of the inner form of a word which was a point laboured by the Russian phenomenologist, Shpet (2006). Another parishioner told me:

Slushayte bozhestvennuyu liturgiyu, vdykhayte eti slova, i pust’ oni otrazhayutsya v vashem tele. Sposobnost’ chuvstvovat’ slova — eto tozhe forma ponimaniya, znayete

Listen to the Divine Liturgy, breathe in those words and let them reverberate through your body. Being able to feel the words is a form of understanding too, you know

Such comments remind us of the effects of vocal production on the experience of embodied selfhood. He went on to remind me that sacred words could have silent, inexpressible meanings where the word is a unity of matter and spirit. Bulgakov (1953, 47/8) referred to this silent meaning, this sense that words can come from within us as their ‘ontological gesture’. By this he meant that it is the ‘ontological gesture’ that comprises the ‘essence’ of the word and that this gesture is provided to us and not determined by ourselves. Words are taken to be incarnations of an essence and that essence is God: words have thus their own ideation according to this understanding.

The symbolist poet, Bely (1910, 240-58), whose views were much aligned with the Russian religious philosophers believed that when a word loses its inner form, the word loses its symbolic meaning. It effectively turns into a raw concept. Svetlana, one of my interlocutors in her sixties, believed that such a word stripped of its symbolism could not serve as a ‘sacred’ word:

Slovo dolzhno imet’ vnutrennyuyu silu. V protivnom sluchaye ono ne mozhet deystvovat’ kak svyashchennoye slovo. Ano dolzhno imet’ eto dopolnitel’noye izmereniye

A word must have an inner force. Otherwise, it cannot act as a sacred word. It must have that additional dimension.

Many ‘sacred’ words do not perhaps come to the surface of phonetic articulation. They remain the inner words of prayer. Bulgakov aspired to a philosophy of language that understood this inner life of words. He was critical of arcane, academic approaches to language that insisted on: konkretnyye oblechennyye v plot’ i krov’ slova(‘concrete words clothed in flesh and blood’) (1953, 9). Instead, he wanted to emphasise the fact that inner words and inner monologues that stem from the darkness of silence do not remain incorporeal. He spoke of the phonetic realisation of words as an ‘incarnation’ (voploshcheniye). Words and images bubble up in our consciousness all the time, and only occasionally appear as external utterances. Bulgakov attempted to understand this kind of complexity inherent to our inner linguistic lives.

We should probably not talk about sacred language in this context without making mention of icons. The church-goers I worked with described the Church Slavonic Language as an icon, and icons can be perceived to enjoy a perlocutionary power and cosmic force (Austin 1962). Austin spoke of the perlocutionary effect of an utterance which refers to the external effect that the utterance has on the hearer. One could think of it as the ability of a word not just to represent reality but also to change it. The icon is the intermediary between the transcendental and the physical world, it is the conduit between form and meaning and thus occupies a liminal existential space. ‘Sacred’ words or words in the liturgical language were perceived by parishioners to be experiential portals in the same way that the icons hanging on the walls of the church were. They were gateways to spirituality, and it was felt that if you changed the language you changed the spirituality of the people.

For Potebnia (1926, 77), words were not so much portals as the locus for the consciousness which navigates the relationship between itself and the world. Potebnia aspired to a philosophy of language that combined sound, meaning and self-knowledge within a unitary word. Such an epistemology of the word was meant to resemble the Holy Trinity where the word is perceived to be a trichotomous experiential structure. He spoke of the content, inner form and outer form of words. The inner meaning was an etymological one, but this is sometimes opaque. He gave the example of stol (table). He claimed that it has an inner meaning because speakers of Russian can detect the etymological association with the verbal root STL meaning ‘to spread’. The association is the ideas of the legs spreading under a flat surface. It should be noted that modern speakers of Russian do not readily make this association.

The physicality of the word

Learning a new language is a magnificent flirt with the spirit of humanity. With a new language in our palms, we grow young again. We start babbling like children, our minds race trying to decline adjectives and conjugate verbs. We become acutely aware of the feel of language and the sensation that the words produce. When we hear people speak another language for the first time, they become for those first fleeting moments someone else entirely. This ability to flit between personae has a great dramaturlogical appeal. In becoming a semi-speaker, you have discovered the acoustic joys of being a quasi-other. This kind of revitalisation that emerges in such a scenario, this phenomenological sense of reducing the rift between words and the body was a preoccupation of some of the Orthodox philosophers. The worshippers I worked with in Moscow also sometimes spoke of the physical presence of sacred words and considered this to be a feature that distinguished this idiom from the vernacular (Russian). In a discussion of Church Slavonic, Svetlanamentioned:

Ya chuvstvuyu, kak eti slova otrazhayutsya v moyem tele. Eti svyashchennyye slova Bozhestvennoy Liturgii. Eti slova iskhodyat ot Boga. Oni nositeli istiny.

I can feel these words reverberate in my body. These sacred words of the Divine Liturgy. These words that come from God. They are the bearers of truth.

The Divine Liturgy was an existentially significant event in the lives of these worshippers and in such a reflexive ethnography of presence, language and idiom choice were implicated in these events. Contrary to Durkheim, such traditionalist worshippers did not perceive the sacred as above all written but it had to be ritually separated from the profane vernacular. As the sacred language of the Orthodox Church, Church Slavonic belongs exclusively to the religious realm just as the vernacular was perceived to belong to the non-religious domain. Russian Orthodox linguistic ideologies emphasize not denotation (Leonard 2021b, 140-58; Panchenko 2019, 167-91), but performance. Idiom choice reinforces the illocutionary force of ritual language and this ritual speech requires a collective consciousness to have its pragmatic effect. Many interlocutors felt that changing the language of church services would dilute or even nullify the illocutionary force of the speech act. It is the stability and fixity of Church Slavonic that renders ritual performance authoritative whereas worshippers held that a constantly changing vernacular would struggle to map such liturgical continuity.

So, in a world of commoditised digital babble that we arguably live in today, how can we return to the physical presence of the word? Rozanov (1970) would have said through ‘spontaneity’, ‘vitality’, ‘creativity’ or by using a language that gives voice to silence, that embodies feelings, the kind of language that makes us feel the personality of the speaker – not written language that is clouded and impartial, but also not verbal noise. Rozanov was looking for some kind of aesthetic renaissance of speech. He wanted to re-ritualise language in some way. Only once speakers had rediscovered the ‘living force’ of language, did he believe listeners would actively impose poetic expectations on its content. Rozanov wanted speakers to understand that ‘language was God given’, that all words could have a sacral authority and thus have a transformative power – surely an implausible concept. He believed that if language could be transformative, it could regain its prophetic status. Without this, he felt we were left with just verbal noise. He insisted that in his time people had lost ‘the spirit of prophecy’.

The issue of losing the sense of a word’s physicality is perhaps an ideological one. The conventionalisation of language means that inevitably it becomes detached to some degree from a sense of immediate, first-hand experience. If you are a learner of Russian for instance, you are more inclined to realise (after probably being prompted) that the word dusha produces a physical mimesis of exhaling breath in its utterance. It is almost like a sigh. Russian religious philosophers and traditionalist Orthodox Christians would, I suspect, agree that this is not coincidental. Once you become a fluent speaker, however, such an awareness of physical mimesis soon dissipates.

If we lose the feel of language in this way, does that mean that it loses its power? Does it have real world consequences? Would it not be easier to enter into the lives of listeners and readers if we maintained the feel of language? Losing the feel for language has real world consequences for Orthodox believers because many subscribe to the notion that sacred words or words uttered in a sacred context retain the imprint of the Divine creation (Eto slovo sokhranyayet na sebe pechat’ Bozhestvennogo tvoreniya). And if this is so, then they have the energy of the Divine logos.

Perhaps the most pertinent question for my interlocutors was what is in fact the relationship between words and belief? Can words be a source for spiritual renewal? One is more aware of the physical presence of words during prayer when words are uttered slowly and with a sense of purpose. Rozanov would have believed that words in this context have this previously referred to ‘living force’. It is at times like this that we can understand perhaps better the idea that ‘language is God given’. This is when language has its energy in its ‘here and now’ – as Merleau-Ponty (2012 [1945]) would have said.

Conclusion

Ern (1911, 114) said that it was inevitable that the conflict between ratio and logos would take place in Russia. The religious cosmologies put forward by earlier Russian thinkers and devout Orthodox Christians should challenge some of our own ways of thinking. Collectively, they turn their back on the triumph of reason. You can believe in rationality, but occasionally you have to ‘rely upon an impersonal, extra-human force’ (Willerslev and Suhr 2018, 73).

This kind of fieldwork has something to tell us about linguistic constructions of personhood. Language contributes to the production of subjectivity, and can shape the bodily hexis of its speakers. Only by taking into consideration Sapir’s (1973, 153) form-feeling, can we begin to understand the meaningful relations between words and reality. Language is a web of experiences, and these personal experiences should be at the centre of language study and not on the distant periphery. Ethnography should surely be about experiencing the reality of things, and not just defining things. ‘The knower should not claim ascendancy over the Known’ (Fabian, 1983, 164) and that applies to language and experience too.

In the Saussurean view, language is structure and words are inert whereas it is clear from their writings that the Orthodox philosophers felt the sensual reality of language. Bulgakov reminds us that for Protestantism the ministry of the word is ‘meaning’ only, but Orthodoxy understands the ‘power’ of the word and this ministry forms the basis of its sacramental life. Words for these Orthodox thinkers were roots of cosmic self-expression and word-symbols are interconnected with the elements of the cosmos itself. They referred to a connection between words, spirituality and the sacred and this connection was not characterised by bipolarity. The rhetoric was that of a new religious consciousness. They believed that if we no longer perceived words as simply shells for entities and instead as symbols, living entities and bearers of energy, then we would be embracing a richer, more holistic and multi-dimensional ideology of language.

Fieldwork amongst Orthodox Christians shows us that an utterance can be charged with a spiritual power and that the voice plays a dialectical role between object and subject. This understanding exists at a subliminal level. If we were to revise our reductionist assumptions about reality, then we might be more open to the idea that language alone can have certain powers.

References

Austin, John Langshaw. 1962. How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures Delivered at Harvard University in 1955. London: Oxford University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin. Edited by Michael Holquist. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bely, Andrei. 1910. “Mysl i iazyk. Filosofia iazyka A. A. Potebni”. Logos: 240-58. https://crecleco.seriot.ch/textes/Belyj10.html

Briggs, Charles. 2014. “Dear Dr Freud”. Cultural Anthropology 29, no.2: 312-43.

Bulgakov, Prot. Sergei. 1953. Filosofiia imeni. Paris: YMCA Press.

—. 1917. Svet nevecherniy: Sozertsaniya i umozreniya. Moscow: Pyt.

Descola, Philippe. 2013 [2005]. Beyond nature and culture. Translated by Lloyd, J. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Originally published as Par-delà nature et culture. Paris: Gallimard.

Durkheim, Émile. 1961. The Elementary forms of the Religious Life. NY: Collier.

Ern, Vladimir. 1911. Bor’ba za Logos. Opyty filosofskie i kriticheskie. Moscow: Put.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and Order: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Faudree, Paja. 2012. “Music, Language and Texts: Sound and Semiotic Ethnography”. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 519-36.

Haeri, Niloofar. 2003. Sacred language, ordinary people. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Harkness, Nicholas. 2014. Songs of Seoul: An Ethnography of Voice and Voicing in Christian South Korea. Berkeley: University of California Press.

—. 2011. “Culture and Interdiscursivity in Korean Fricative Voice Gestures”. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology21, no.1: 99-123.

Jacobsen-Bia, Kristina. 2014. “Radmilla’s voice: Music Genre, Blood Quantum and Belonging in the Navajo Nation”. Cultural Anthropology 29, no.2: 385-410.

Jakobson, Roman and Hrushovski, Benjamin. 1980. “Roman Jakobson: Language and Poetry// Sign and System of Language: A Reassessment of Saussure’s Doctrine” Poetics Today 2 (1a): 33-38.

Kunreuther, Laura. 2014. Voicing Subjects: Public Intimacy and Mediation in Kathmandu. Berkeley: University of California Press.

—. 2006. “Technologies of the Voice: FM Radio, Telephone and the Nepali Diaspora in Kathmandu”. Cultural Anthropology 21 (3): 323-53.

Leonard, Stephen Pax. 2021. “Experiencing Speech: Insights from indigenous Ideologies of Language”. International Journal of Language Studies 15(1): 1-26.

—. 2021b. “Secularisation of the Word: The Semiotic Ideologies of Russian Orthodox Bloggers”. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 20 (60): 141-58.

Lindholm, Charles. 2002. “Authenticity, Anthropology, and the Sacred”. Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 75, No.2: 331-38.

Losev, Aleksei. 1990. Filosofiia imeni. Moscow: Izd. Moskovskogo universiteta.

Luehrmann, Sonja. 2017. “God values Intentions: Abortion, expiation, and moments of sincerity in Russian Orthodox pilgrimage”. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7 (1): 163-84

Malinowski, Bronisław. 1923. “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages.” In The Meaning ofMeaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism, edited by Charles Ogden and Ivor Richards, 296-336. London: Kegan Paul. (Fourth edition revised 1936)

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2012 [1945]. Phenomenology of perception. Translated by Landes, Donald. A. Originally published as Phénoménologie de la perception (Paris, Gallimard). London and New York: Routledge.

Ochs, Eleanor. 2012. “Experiencing language”. Anthropological Theory 12 (2): 142-160.

Panchenko, Alexander. 2019. “Nevidimyye partnery i strategicheskaya informatsiya: chenneling kak ‘semioticheskaya ideologiya’”. Gosudarstvo, religiia, tserkov’ v Rossii za rubezhnom 37 (4): 167-91.

Part, Naftali. 1979. “Orthodox philosophy of language in Russia”. Studies in Soviet Thought 20 (1): 1-21.

Potebnia, Alexander. 1976. Estetika i poetika. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

—. 1926. Mysl’ i jazyk. Kharkov, 1862, rpt. Kiev: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel’stvo Ukrainy.

Rozanov, Vasily. 1970. Izbrannoe: Uyedinennoye, Opavshiye list’ya, Mimoletnoye Apokalipsis nashego vremeni, Pis’ma k E. Gollerbakhu. Munich: A Neimanis.

Sapir, Edward. 1973. ‘The Grammarian and His Language’. In Selected Writings in Language, Culture and Personality edited by David G. Mandelbaum, 150-60. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Schütz, Alfred and Kersten, Fred. 1976. “Fragments on the Phenomenology of Music”. In Music and Man, edited by Frederick Kersten, 5-71. London: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers.

Shpet, Gustav. 2006. Vnutrennjaj forma slova: etudi y variatsi na temi Humboldta. Moskva: URSS.

https://gachn.de/files/data/Shpet_Vnutrenyaya_forma_slova_Vip._7.pdf

Summerson Carr, E. 2013. “Signs of the Times: Confession and the Semiotic Production of Inner Truth”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19 (1): 34-51.

Weidman, Amanda. 2014. “Anthropology and Voice”. Annual Review of Anthropology Vol 43: 37-51.

—. 2006. Singing the Classical, Voicing the Motion: the Post-Colonial Politics of Music in South India. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Willerslev, Rane. and Suhr, Christian. 2018. “Is there a place for faith in anthropology?: Religion, Reason and the Ethnographer’s Divine Revelation”. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 8 (1/2): 65-78.